What is Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)?

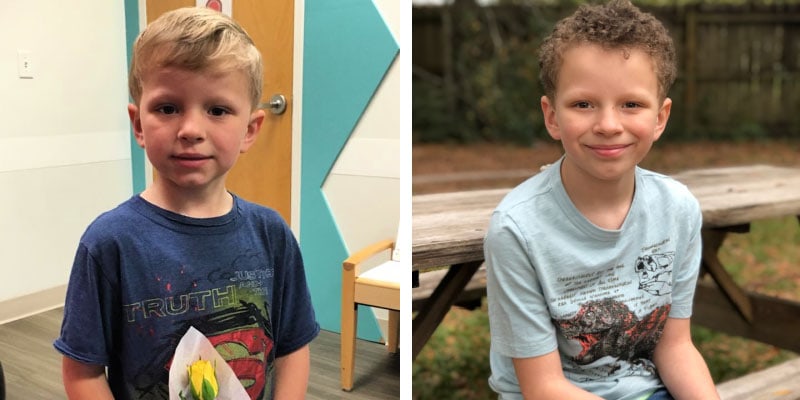

Rally Kid Kohlton has courageously fought LCH since the age of 2. His symptoms began as bumps on his forehead that turned out to be tumors.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disorder in which the body produces an overabundance of Langerhans cells. These cells, which are also known as histiocytes, are a type of white blood cell that helps the immune system fight off infections.

LCH causes too many of these cells to form, ultimately resulting in a buildup in the body. This accumulation of cells then damages organs, forms tumors, and otherwise disrupts normal tissue functions. According to the Histiocytosis Association, approximately one in 200,000 children is diagnosed with LCH.

LCH is classified into three syndromes:

- Eosinophilic granuloma: the most common type that occurs most often in children who are five to 15 years of age

- Hand-Schüller-Christian disease: a chronic form of LCH that is typically diagnosed before the age of five

- Letterer-Siwe disease: a rare and potentially fatal syndrome that affects children under the age of three

Doctors and researchers aren’t entirely sure what causes LCH. Its classification as a cancer has been debated because the symptoms vary so widely, and chemotherapy is not always necessary. Research suggests LCH is a type of neoplastic disease, causing abnormal cell growth that results in benign, pre-cancerous or cancerous tumors.

More recent studies have found mutations—typical of cancer cells—in the genes that control Langerhans cells. This research revealed that up to two-thirds of LCH patients have alterations in the BRAF gene, which is responsible for making proteins involved in cell growth.

It is important to note that LCH is not believed to be a hereditary disease.

LCH SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

There are many signs and symptoms associated with LCH, which often affects the skin and bones but can also involve lymph nodes and/or major organs. Symptoms depend on the age of the patient and the specific type of LCH.

Rally Kid Shelby had been sick on and off for most of her young life. When a CAT scan of her skull indicated a potential infection, pathology ultimately revealed it was LCH.

According to Kenneth L. McClain, MD, Ph.D., the Director of the Histiocytosis Program at Texas Children’s Cancer and Hematology Centers, “Patients may develop itchy or scaly rashes, sores on the inside of the cheeks and on the tongue, swollen gums and loose teeth.” Dr. McClain continued, “They can also experience chronic drainage from the ears, bone pain in any location, chronic cough or trouble breathing, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain and excessive thirst and urination.”

LCH DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Diagnosing LCH is not always straightforward because the symptoms are so varied and can sometimes be attributed to other illnesses. Complete medical diagnostic testing is required and might include x-rays of the affected area, MRIs, CT scans, a complete blood count with blood chemistry test and a bone marrow biopsy.

Treatment will also vary based on the severity of the patient’s LCH. A mild case where no other organ systems are affected will require only minimal treatment at the site of affliction. A slightly more severe case might call for mild chemotherapy treatment for up to a year. Finally, the most aggressive cases of LCH typically require high doses of inpatient chemotherapy, and in some cases, a bone marrow transplant.

Overall, the prognosis for LCH is good. Many children with less severe cases are able to be cured. Survival rates in more severe cases—usually involving multiple organs—is closer to 80%. These children are also more likely to experience long-term side effects from the disease, the treatment or both.

“Not all patients respond well to our first treatments, so we need additional plans,” explained Dr. McClain.

Kohlton has relapsed six times and endured seven year-long chemotherapy protocols—each more intense than the last.

“If your child is diagnosed with LCH, find a pediatric oncologist who has treated several children with this disease,” recommends Dr. McClain. “Reach out to the Histiocytosis Association of America, which has many ways of supporting families. You can also view my article in the National Cancer Institute PDQ for more information.”

Dr. McClain recommends that patients and parents ask a lot of questions and seek expert opinions. “Most LCH patients can now be cured,” he asserted. “The frustration is that some patients have recurrences and need to be re-treated.”

LCH RESEARCH

More research is needed to uncover the cause of LCH and discover why the symptoms—and related treatments—can vary greatly. Still, one of the reasons why the prognosis for LCH patients is so promising is due to recent advancements in research and treatment.

In addition to seeing patients, Dr. McClain is involved in a number of clinical studies, including new therapeutic interventions for LCH. (Photo credit: Tom Spoth, Texas Tribune)

“There is a new group of drugs which specifically attack LCH cells with certain mutations,” Dr. McClain shared. “These drugs are known as BRAF or MEK inhibitors, meaning they block the mutations. They work very well in making the patient better, but unfortunately do not completely eliminate the disease-causing cells.”

Current biologic studies in Dr. McClain’s lab are focused on determining the gene expression profiles of Langerhans cells and lymphocytes from control and patient tissues then making clinical correlations.

JOIN THE FIGHT AGAINST LCH

Children with LCH are counting on research to give them hope for a future after cancer. Rally Foundation is funding some of the most innovative and cutting-edge childhood cancer research. Give in honor of kids like Kohlton and Shelby. Please make a donation today.

Kids like Shelby deserve #MoreThan4 percent of federal funding for childhood cancer research.

0 Comments